Tonga’s eruption: From tsunami warnings to Sonic Booms

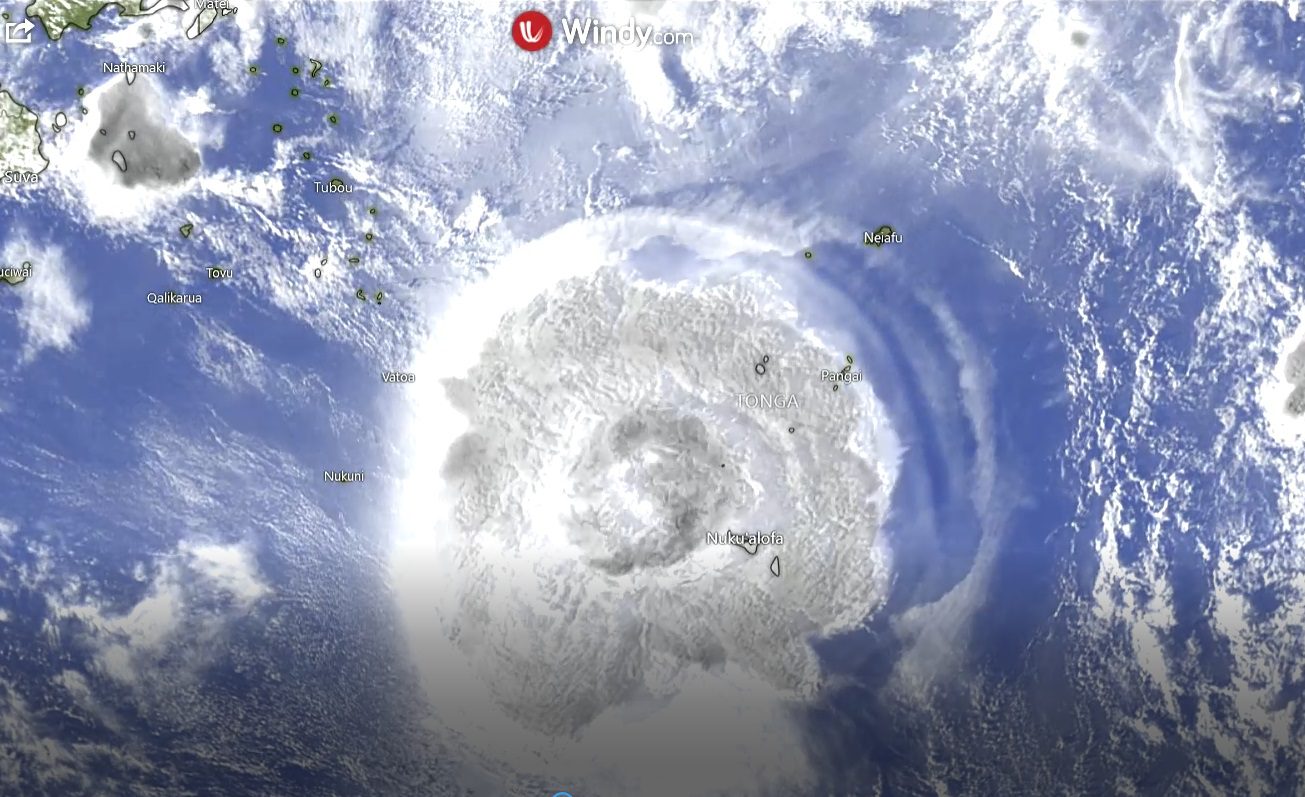

The eruption of the volcanic plume produced record amounts of lightning, before generating a blast heard thousands of miles away. Here are the geologists’ explanations for the event and what might happen next.

A submarine volcano, identified by two small uninhabitable islands within the Kingdom of Tonga, began to erupt just a few weeks back. The initial eruption appeared innocuous with light plumes and moderate explosions. Few people outside the archipelago were aware of it.

However, the volcano Hunga Tonga Ha’apai (or Hunga Tonga Ha’apai) has made the world sit up and pay more attention over the past 24 hours.

Its eruptions became more violent after a brief period of calm earlier in the month. Satellite imagery showed that the middle of the island disappeared. Record-breaking lightning was produced by towering columns made of ash.

Chris Vagasky is a meteorologist and lightning application manager at Vaisala, a Finnish weather measurement company. “We started to receive 5,000 or even 6,000 events per hour. It’s about a hundred events every second. It’s unbelievable.”

On January 15, at dawn, the volcano erupted in a massive explosion. The shockwave that radiated outward at the speed of sound, blasted the atmosphere out of the way. The shockwave travelled halfway around the globe, reaching as far as the United Kingdom (which is a staggering 10,000 miles away).

To everyone’s horror, a tsunami quickly followed. Tongatapu was the main island of the kingdom and home to Nuku’alofa the capital, which is located just a few miles south of the volcano. As the streets began flooding, communications were disrupted and people fled their homes to save their lives. Although smaller tsunami waves rushed across the ocean to parts of the Pacific Northwest, they caused surges in Alaska and Washington State. Minor tsunami waves were also recorded at stations in California, Mexico, South America, Australia, New Zealand and other locations.

Stay safe everyone 🇹🇴 pic.twitter.com/OhrrxJmXAW

— Dr Faka’iloatonga Taumoefolau (@sakakimoana) January 15, 2022

Recent research into the geologic history suggests that a powerful eruption is a rare event. It is only one in every 1,000 years, according to recent studies. It is hoped that the worst of the eruption will be over. Even if this is true, the damage is already done.

Janine Krippner from the Smithsonian Institution’s Global Volcanism Program, a volcanologist, says that Tonga is facing a potentially catastrophic event. It makes me sick just thinking about it.

Scientists and the public, both anxious to find out what caused this eruption and what might happen next, are both eager. Because the volcano is so remote and hard to see up close, information has taken a while to come out.

Krippner states that there are more questions than answers. Here’s what scientists know about the tectonics and geologic forces involved and what this might mean for the future of the volcano.

The Pacific’s volcanic powerhouse

Hunga Tonga Ha’apai can be found in the South Pacific region that’s crammed with volcanoes, some above the waves and others below the water level. These volcanoes have a tendency to erupt violently. In the past, events have seen volcanic eruptions that have blown themselves apart and created new islands.

Around 1,500 active volcanoes are found all over the globe. Find out about the main types of volcanoes and the geological processes behind eruptions. Also, find out where the most devastating volcanic eruptions have occurred.

The Pacific plate’s constant dive below the Australian tectonic plates is what causes this profusion of volcanoes. The water in the slab sinks into the superhot mantle rocks, where it is heated up and then rises to the top. These rocks will melt more easily if they are given water. This results in a lot of magma, which is sticky and full of gas. It can be a recipe for explosive eruptions.

Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha’apai follows this pattern. These bits of land are situated above a volcano that is more than 12 miles in width. It has a cauldron-like hole measuring three miles in diameter, which is hidden from the view of the sea. The volcano has been seen rising with vigour and vim since 1912, occasionally rising above the waves before being eroded away. It was created by the eruption of 2014-15 and became a stable island, which soon became home to barn owls and colourful plants.

Hunga Tonga Ha’apai began erupting on December 19, 2021. It produced a series of blasts, an ash column 10 miles high, but nothing out of the ordinary for a submarine volcano. Sam Mitchell, a volcanologist from the University of Bristol, said that the volcano generated enough lava to expand the island by almost 50 per cent over the next few weeks. The volcano seemed to be slowing down as the new year began.

In the final days of the trial, things turned dramatic.

The menacing maelstrom of the volcano

The volcano’s explosiveness began to increase, and the lightning that emerged from its ashy plume began to eclipse the previous eruptions.

Lightning can be produced by volcanoes because the ash particles from their plumes bump into one another or into bits and ice in the atmosphere. This creates an electric charge. Lightning flashes are caused by positive charges being segregated from the negative. Learn more about lightning triggers from volcanoes.

Vaisala’s GLD360 network detected the Tonga eruption’s lightning from the beginning. This global network uses radio receivers to detect lightning in intense bursts. The system picked up a few hundred to a few thousand flashes every day for the first two weeks. This is not unusual. Vagasky says, “It was clearing its throat, I suppose.”

Last night, there was no other place on earth that felt as electric as this.

CHRIS VAGASKYVAISALA METEOROLOGIST

The volcano had produced tens to thousands of discharges by Friday night and Saturday morning. This Tongan volcano produced 200,000 discharges per hour at one time. Comparatively, the 2018 eruption at Indonesia’s Anak Krakatau produced 340,000 releases in a matter of days.

Vagasky says, “I couldn’t believe the numbers that I was seeing.” You don’t see it with a volcano. This is something different. It was like there was nothing else on earth last night that was as electric.”

Although it may have appeared spectacular from far, up close, it would have been apocalyptic. A constant stream of light, thunder, and volcanic bellows would be the soundtrack. The plume of lightning didn’t just strike the sky, but the ground and ocean as well. Vagasky says that this was dangerous for anyone who was sitting on Tongan islands because there is lightning all around them.

So, why is this eruption causing a record-breaking amount of discharges?

Kathleen McKee, a volcano-acoustic researcher at Los Alamos National Lab, New Mexico, said that water always increases the chances of lightning strikes. Magma mixed with water in shallow bodies of water can cause it to become vaporized. This causes magma to explode into millions of tiny pieces. Lightning is more powerful than the finer and more abundant particles you have.

Corrado Cimarelli is an experimental volcanologist at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. The heat of the eruption transports water vapour into the lower, colder reaches of the atmosphere where it becomes ice. This provides plenty of particles for the ash and ash to interact with, and produce electricity.

However, it is not possible to know why this eruption produced so much lightning. Cimarelli states that the volcano is far away and that there are no constraints on the atmospheric profiles near the plume.

The Hephaestion Hammer falls

The volcano’s cataclysmic eruption was not only preceded by an incredible amount of lightning. Satellite imagery showed that the island had stopped building itself by Saturday morning. The explosion had likely caused the volcano’s middle to disappear.

The shockwave that erupted at the end unleashed a huge explosion and ricocheted around the globe at breaking speeds. The tsunami followed immediately, crashing into many islands of the Tongan archipelago and racing across the Pacific.

Jackie Caplan-Auerbach is a volcanologist and seismologist at Western Washington University in Bellingham. She says that the tsunami was caused by a massive amount of energy. However, there are not enough data to determine the exact cause.

These events require water to be displaced. This can happen by underwater explosions or a collapse event when lots of rock fall from the volcano into the ocean.

Scientists will need to collect more indirect data as the ash column is covering the volcano and much of it submerged underwater before they can draw any conclusions. The blast’s acoustic waves or the redistribution mass around the volcano could provide clues.

Caplan-Auerbach states that “the jury is still out”, but the fact that an intense eruption and powerful tsunami emerged from a single volcanic island “speaks to how incredible the power of this eruption.” The shockwave, which was caused by the rapidly moving air hitting the ocean, was strong enough to cause water to flow out of the way. This phenomenon is known as a meteo tsunami.

In a blog post, Shane Cronin (a New Zealand volcanologist) states that the volcano’s chemistry is a clue as to why it was so intense. This changes over time as the magmatic fuel inside evolves.

Like many other volcanoes, this one must replenish its magma storage after a major eruption. Since the last eruption in the area was in 1100, molten rocks have been building up at depth. It becomes more full and magma slowly leaks out from the volcano. This is what has caused the numerous eruptions since 2009.

Cronin states that once the magma has been recharged, it starts to push gas pressures up too fast for small eruptions to release them. When magma finds an opening in the magma reservoir, it depressurizes, and much of it is then evacuated in one blast.

A cloudy future in Tonga

Although the Tongan archipelago is believed to have been created by infernal forces, it is clear that the high cost of living there can make it difficult for people to afford. The kingdom is home to only 100,000 people, about 25% of which live in the capital. They are currently being ravaged by tsunami and ashfall waves.

Krippner states that the biggest unknown at the moment is how Tonga’s people are. This eruption could potentially prove to be devastating for the country.

Now comes the big question: “Is this eruption finished?” Krippner answers. “We don’t know.”

Mitchell suggests that such a frightening eruption could be the result of the effective decapitation of the volcano’s magma reservoir and the rapid exsanguination of its molten contents. Volcanologists will continue to study this eruption, which will help them understand future events and aid in mitigation efforts.

It’s impossible to predict how the eruption will play out. So for now, all eyes remain firmly fixed on Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai.

Thanks be to God not near in the Philippines and nothing got hurt GOD BLESS US ALL AMEN.