5 Incredible Facts About Feather Stars

Introduction

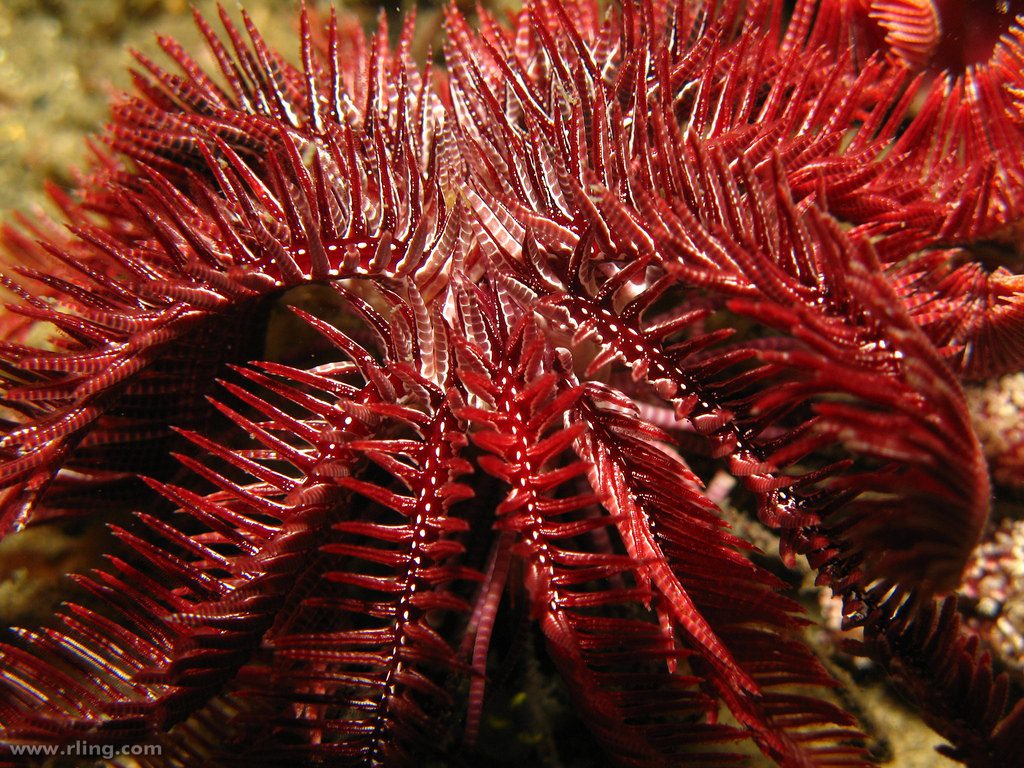

These strange, plant-like creatures are hidden among bright corals or anemones. Their slender, branching legs billow like colourful, fern fronds.

Things get a little weird when they break away – you can swim, flounder, or walk through the ocean like an apocalyptic Triffid.

Description

These are crinoids. They are part of the echinoderm family, including sea stars, sea urchins, and other creatures.

There are approximately 600 species of Crinoids on Earth. They can be found in shallow seas and deep at depths up to 9,000m.

They can be found all over Australia, from the mysterious eastern abyss stretching from Launceston and Brisbane to the Great Barrier Reef to the west coast.

While they may have stalks attached to the seafloor as juveniles (crinoids), they often lose them as adults and become free-swimming organisms.

Sea lilies are the species that retain their stalks to adulthood. They look similar to underwater flowers.

Feather stars can still use a set of tiny legs called “cirri” to anchor themselves to substrate and rocks if necessary.

These lovely, fringed arms are covered with tiny, mucus-secreting tube feet. This allows the feather stars to catch plankton as well as other microscopic morsels in the water.

How Do Feather Stars Feed?

However, how they get the food in their mouths is another story. Sara Mynott, a UK marine biologist at the University of Exeter, explains this for Nature.

They start by cleaning the foot closest to the mouth. Next, they clean the foot below it. Then, wrap the mucus-filled snack in a towel and transport it foot by foot along the arm.

The following foot below wraps around it and scrapes off the food for a second.” This continues down the arm of the feather stars, creating a bolus that gradually grows in size.

The bolus eventually reaches the mouth, where it is ingested in a U-shaped stomach.

The horseshoe gut is crucial because it allows the feather star’s anus to be placed next to its mouth.

Although feather stars can move, they are very rarely seen doing so. Until recently, it was believed that they were slow-moving.

Scientists used to believe that feather stars could only move half a metre per hour. However, one was able to clock speeds of up to 5 cm/second (up to 180 metres per hour) in 2005.

Crinoids are passive suspension feeders that filter plankton from the seawater flowing by them. They have feather-like arms and filter small particles of debris. The arms rise to form a fan shape that is perpendicularly held by the current. Mobile crinoids perch on rocks and coral heads to maximise their food opportunities.

The food particles are caught by the main (longest) tube feet, which are completely extended and held erect from the pinnules, producing a food-trapping mesh. In contrast, the secondary and tertiary tube feet are involved in manipulating anything encountered.

Sticky mucus covers the tube feet and traps all particles that come into contact. Once they have captured a food particle, the tube feet move it towards the ambulacral groove where the cilia propel the mucus along with food particles towards the mouth.

The mucus stream is held in place by the lappets located at either side of the groove. The food-trapping surface can be quite long. For example, the 56 arms of a Japanese sea lily with 24 cm (9in) arms have a length of 80m (260ft), including pinnules.

Mostly speaking, crinoids living in environments with relatively little plankton have longer and more highly branched arms than those living in food-rich environments.

The mouth drops into the oesophagus. The stomach is not real, so the oesophagus connects to the intestine. It runs in one loop around the inside calyx. Diverticulae in the intestine can be either long or branched.

The rectum is a muscular opening at the end of your intestine. The anus is located at the edge of the tegmen and rises from this conical protuberance. Faecal waste is formed into large, mucous-cemented pellets, which descend onto the tegmen and then the substrate.

Feather Star Reproduction and the life cycle

Although crinoids cannot clone like starfish or brittle stars, they can replace lost body parts. Arms can be regenerated after being damaged by predators or other adverse environmental conditions. Even the visceral mass can also regenerate in a matter of weeks. This regeneration is crucial in the survival of predatory fish attacks.

Crinoids can be either male or female and are dioecious. The gonads of most species are found in the pinnules. However, in some species, they can be found in the arms. Some pinnules may not be reproductive.

The gametes are created in the genital canals that are enclosed in genital coeloms. The pinnules eventually burst to allow the sperm, eggs and sperm to escape into the seawater. The fertilised eggs in some genera, like Antedon, are cemented to the arms using secretions from epidermal glands.

In others, particularly Antarctica’s cold water species, the eggs are brooded in pinnules or specialised sacs on their arms.

The fertilised eggs hatch to produce free-swimming vitellaria larvae. The larvae are barrel-shaped and have cilia rings running around the body. There is also a tuft sensory hairs at its upper pole.

While feeding (planktotrophic) and non-feeding (lecithotrophic) larvae exist among the four other extant echinoderm classes, all present-day crinoids appear to be descendants from a surviving one clade that went through a bottleneck after the Permian extinction, at that time losing the larval feeding stage.

The larva’s free-swimming period lasts for only a few days before it make a home on the bottom and attaches itself to the underlying surface using an adhesive gland on its underside. After becoming radially symmetric, the larva undergoes a prolonged period of metamorphoses to become a stalked juvenile.

Even the free-swimming feather stars go through this period, with the adult eventually breaking away from the stalk.

How Do Feather Stars Move?

Modern crinoids (i.e. the feather stars) are free-moving and do not have a stem like adults. Marsupitsa (Saccocoma), Uintacrinus, and Saccocoma are examples of fossil crinoids thought to be free-swimming. Such a movement may be induced concerning a change in the current direction, the need to climb to an elevated perch to feed, or because of an agonistic behaviour by an encountered individual.

Crinoids can also swim. This is done by coordinating repetitive sequential movements of the arms in three different groups. The direction of travel initially is upwards, but it soon turns horizontal.

The speed is approximately 7 cm (2.8 in) per second with the oral surface in front. Swimming is usually performed in short bursts lasting less than a minute. In Florometra serratissima, it only occurs after mechanical stimulation or an escape response from a predator.

A 2005 recording of a stalked crinoid pulling itself along the Grand Bahama Island’s seafloor was made. Although stalked crinoids can move, the fastest known stalked crinoid motion was only 0.6 metres (2 ft) per hour.

One of these crinoids was recorded moving more quickly, 4 to 5 cm (11.6 to 2.0 inches) per second. This is 144 to 180 meters (472 to 591 feet) per hour.